YIDDISH DANCES ON FILM is devoted to remembering, teaching, and continuing Yiddish Dance, the folk dance of Yiddish-speaking Jews. It developed, along with a rich culture and spoken and gestural language, during 1000 years of life in Eastern Europe. Dance, as it had been even in Biblical times, is an important part of Jewish and Ashkenazic expressive cultural heritage. Although often endangered, dance continues to live no matter how Judaism is practiced, as well as for over a century on the stage in plays and in concert dance. Here are three films that capture some of the essence of Yiddish folk dance expression in three different ways.

Karen

Goodman

Come Let Us Dance

(Lomir Geyn Tantsn)

Two Yiddish Dances

Heritage, Style & Steps

PRODUCED, WRITTEN, DIRECTED by KAREN GOODMAN

(2022)

This documentary/instructional video provides an accessible resource for learning the basics of Yiddish Folk Dance. It delves into the steps and flavor of the folk dances of the Yiddish speaking Jews of pre-war Eastern Europe, that were such an integral part of Jewish life.

MIRIAM ROCHLIN (1920, Bonn – 2012, Los Angeles) teaches variations of classic dances the Freylekhs and the Sher step by step along with her valuable insights into what gives them their unique character.

The dances are based on the 1942 book, TEN JEWISH FOLK DANCES, (1942) by NATHAN VIZONSKY (1898, Lodz – 1967, Los Angeles)

Dybbuk Remix:

Dancing Between Worlds

“Dybbuk Remix: Dancing Between Worlds” began as a spontaneous, site-specific dance improvisation to music playing in the former synagogue of Kazimierz Dolny, Poland. Part of diasporic Jewish identity is the ongoing site-specific negotiation between the past and what creates and binds identity in the present. The film’s title comes from the play by S. An-sky, “The Dybbuk, or Between Two Worlds” (1915), as well as the 1937 Yiddish language film, “The Dybbuk.” Its points of departure are my previous work documenting Yiddish dance and the 1937 film, long a reference for authentic Yiddish folk and ecstatic dance. In this film too, the mysterious sense of the porous borders between spirit and body, past and present, life and death, remembering and imagining, are evoked.

PRODUCED, DIRECTED, PERFORMED by KAREN GOODMAN

(2021)

A Few Thoughts on Yiddish Dance:

Dance has always been a part of Jewish life. In Torah and Talmud it was written of and it remains part of religious practice and celebration no matter where Jews live.

Yiddish dance contains the gestures and flavor of the rich and unique Yiddish culture built over the course of 1000 years. Like the language, the dances are often European folk dance filtered through Jewish practice and perspective to create its own style. Its qualities range from joyousness to quiet theatricality and bravura to meditation and is a combination of passion and reserve required by religious tradition, the times and life itself.

Style lives in the how you do even the simplest things—a hand or shoulder, the expression of mood and emotion the weight of a step. Read the old stories. Look at the old movies. Feel that Klezmer music – how could you not?

Dance.

The Filmmaker

Come Let Us Dance was produced, written and directed in 2001-2002 by Karen Goodman, a critically acclaimed dancer and choreographer, recipient of honors that include a National Endowment for the Arts Choreographer’s Fellowship in 1990, the 1998 Lester Horton Award for Outstanding Achievement in Individual Performance and the 2005 Detroit Jewish Women in the Arts Award for this documentary.

She presented clips from Come Let Us Dance at the 16th Annual World Congress on Dance Research, devoted to Dance As Intangible Heritage, organized by the International Dance Council-UNESCO, Corfu Greece, October 2002, shortly after its release. She writes and speaks on Yiddish Dance and its 20th century champions and interpreters for the stage. She continues to interview and document current teachers and performers to create a video archive to sustain the knowledge of Yiddish dance and gesture.

[GOODMAN’S CHOREOGRAPHY] …MAKES US SEE THE ART AS A WAY BACK TO THE SENSE OF PHYSICAL AND SPIRITUAL UNITY MISSING IN OUR CULTURE.

– Los Angeles Times

KAREN GOODMAN PRESENTS THE RICH FOLK TRADITION OF YIDDISH DANCE IN AN EXQUISITELY BEAUTIFUL AND ARTISTICALLY SENSITIVE WAY.

– Miriam Koral, Executive Director, The California Insititute for Yiddish Culture and Language, Los Angeles

GOODMAN’S PRECIOUS VIDEO ALLOWS US TO RECONNECT WITH THE IMPORTANT–AND THANKS TO GOODMAN, WELL-PRESERVED–PIECE OF OUR HERITAGE.

– Lolly Gold & Deborah Biasca, co-directors, Boulder Yiddish Vinkl, Boulder, CO

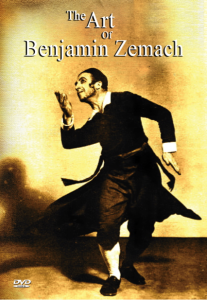

Benjamin Zemach (1901, Bialystok -1997, Israel), was a member of Habima Theatre in its ground-breaking days in 1920s Moscow, and an important actor, dancer, choreographer, director and teacher of both theater and dance in Europe, the U.S., Israel and beyond. He studied in Moscow with Stanislavsky, Vakhtangov, Meyerhold, and in early European modern dance and Russian ballet.

Benjamin Zemach (1901, Bialystok -1997, Israel), was a member of Habima Theatre in its ground-breaking days in 1920s Moscow, and an important actor, dancer, choreographer, director and teacher of both theater and dance in Europe, the U.S., Israel and beyond. He studied in Moscow with Stanislavsky, Vakhtangov, Meyerhold, and in early European modern dance and Russian ballet.